The Challenge: How to Invade Sicily Without It Being Obvious

By early 1943, the tide of World War II had begun to shift. The Allies had secured North Africa and were preparing for their next major move: the invasion of Sicily. This Mediterranean island would provide an essential foothold for the Allied push into mainland Europe through Italy, what Winston Churchill called “the soft underbelly” of Hitler’s Europe.

There was just one problem: Sicily was the obvious target. The Germans knew it, the Allies knew they knew it, and a direct assault without deception would result in catastrophic casualties. Allied leadership estimated potential losses of up to 10,000 men if German defenses were fully prepared.

The question became not whether to invade Sicily, but how to convince the Germans to look elsewhere. The solution would become one of the most remarkable deception operations in military history.

The Trout Memo: Fishing for Ideas

The genesis of Operation Mincemeat can be traced back to what was known as the “Trout Memo,” a document produced in 1939 by Rear Admiral John Godfrey, the Director of Naval Intelligence, with significant input from his assistant, a young intelligence officer named Ian Fleming (who would later create James Bond).

The memo, officially titled “Suggestions for Special Operations,” contained 51 ideas for deceiving the enemy, comparing deception tactics to fly fishing techniques used to catch trout. Item #28 in this catalog of deception suggested planting false documents on a corpse that would wash ashore in enemy territory.

The idea remained dormant until Charles Cholmondeley, a Flight Lieutenant in MI5, revisited it in 1943. Working with Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu of Naval Intelligence, they developed the concept into a full-fledged operation that would target Spanish shores – knowing that though Spain was technically neutral, Franco’s fascist government maintained close ties with Nazi Germany, and German intelligence had a strong presence there.

Creating Major William Martin: A Masterclass in Deception

The first hurdle was finding a suitable body. Through discreet medical channels, the team located a recently deceased man who had died from pneumonia, with fluid in his lungs that would reasonably mimic the appearance of drowning. Out of respect for his family, his real identity has remained protected, though we now know he was Glyndwr Michael, a Welsh laborer who had died after ingesting rat poison, either accidentally or deliberately.

With the body secured and preserved in dry ice, the team began the painstaking process of creating a complete identity for “Major William Martin” of the Royal Marines. This wasn’t simply a matter of creating identification papers – they needed to build an entire life.

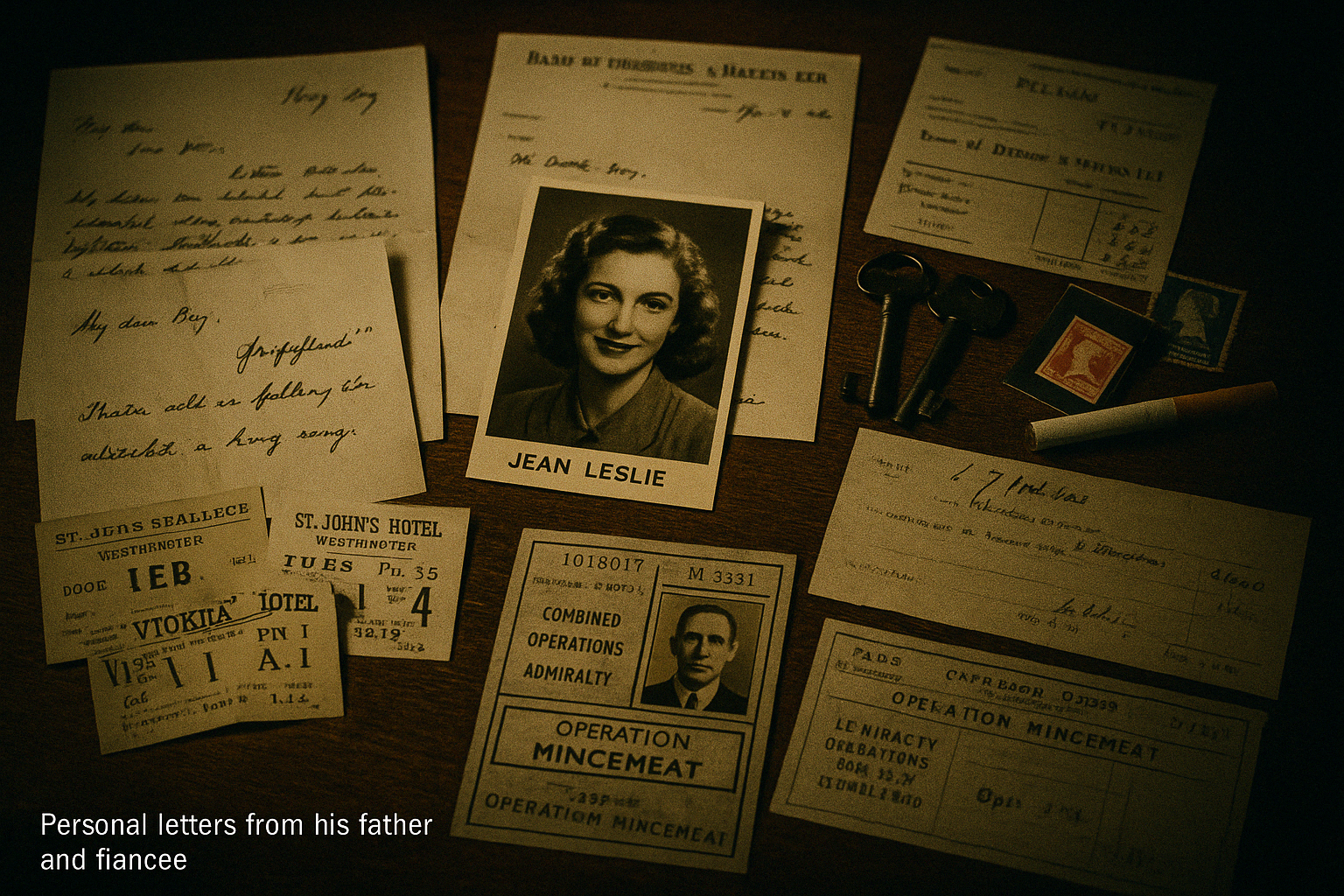

Major Martin received:

- Personal letters from his father and fiancée

- Photographs of his “girlfriend” (actually an MI5 clerk named Jean Leslie)

- Theater ticket stubs

- Hotel bills

- A letter from his bank manager regarding an overdraft

- Keys, cigarettes, and stamps

- A receipt for an engagement ring

- Official ID card and security passes

Each item was carefully aged to appear genuinely used. Montagu even carried Martin’s wallet in his pocket for weeks to create wear patterns. The attention to detail was extraordinary – they included a letter from the jeweler who had sold Martin his “fiancée’s” engagement ring, mentioning that the ring would be ready for collection upon his return.

The Crucial Documents: Misdirection in Plain Sight

While the personal items established Martin’s identity, the real purpose of the operation lay in the official documents he carried. Tucked into his briefcase was a personal letter from Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Nye, Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff, to General Harold Alexander, who was commanding in North Africa.

The letter mentioned, almost as an aside, concerns about the upcoming operations in Greece and Sardinia, casually naming them as the targets instead of Sicily. It also contained other military matters to ensure it didn’t seem too obvious – it needed to seem important enough to be classified but not so perfect that it would raise suspicion.

A second letter from Lord Louis Mountbatten added further credibility by mentioning a “sardine” joke – a deliberate hint at Sardinia that seemed natural in context but would stand out to German intelligence analysts.

The Journey: HMS Seraph and Operation Mincemeat

On April 19, 1943, the British submarine HMS Seraph departed Holy Loch in Scotland with its unusual cargo. Commanded by Lieutenant Bill Jewell, the submarine made its way to the Spanish coast near Huelva, chosen because the currents would naturally carry a floating body to shore and because it was known to have a German agent operating in the area.

In the early hours of April 30, the submarine surfaced off the Spanish coast. In a solemn moment, Lieutenant Jewell read a passage from the Psalms over the body before “Major Martin” was gently lowered into the water, equipped with a life jacket to ensure he would float and eventually wash ashore.

The Spanish Connection: Germany Takes the Bait

As anticipated, the body was discovered by a local fisherman later that morning and brought to Spanish authorities. The British Naval Attaché in Spain, Alan Hillgarth, was informed and began pressing for the return of the classified documents – applying just enough pressure to convince the Spanish (and by extension, the Germans) of their importance without overplaying his hand.

Spanish officials performed an autopsy, concluding that the cause of death was drowning following a plane crash at sea – exactly as the British had planned. More crucially, before returning the documents to British authorities, the Spanish shared them with Adolf Clauss, the German intelligence agent in Huelva.

The Germans photographed the documents and sent the images to Berlin for analysis. Their suspicions were not raised, partly because British intelligence had previously established a pattern of sensitive information traveling by courier rather than radio transmission for security reasons.

Hitler’s Decision: The Deception Succeeds

Through Ultra, the Allies’ secret program that had broken German military codes, British intelligence soon received confirmation that their deception had succeeded beyond their wildest expectations. The documents had reached Adolf Hitler himself, who became convinced that Greece and Sardinia were indeed the Allied targets.

On May 12, 1943, Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 48, ordering reinforcements to Greece and Sardinia at the expense of Sicily. He moved the formidable 1st Panzer Division from France to Greece, repositioned minefields, and transferred air and naval units to defend against the phantom invasion.

Operation Husky: The Real Invasion

When the actual Allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) began on July 10, 1943, German forces were caught flat-footed. Despite some challenging weather conditions and the inherent difficulties of amphibious operations, Allied forces secured beachheads with considerably fewer casualties than anticipated.

Even as evidence mounted that Sicily was indeed the target, German High Command remained skeptical, believing for some time that the Sicily landings were merely a diversion from the “real” attack on Greece or Sardinia. This hesitation proved crucial, delaying the deployment of reinforcements until it was too late.

Sicily fell after 38 days of fighting. The success of the invasion led directly to the fall of Mussolini’s fascist government and, eventually, to Italy’s surrender on September 3, 1943. Hitler was forced to divert significant resources to shore up the Italian front, weakening German positions elsewhere in Europe.

The Aftermath: Impact and Legacy

Operation Mincemeat is widely regarded as one of the most successful deception operations in military history. Its impact extended far beyond the immediate tactical advantage gained in Sicily:

-

Strategic Impact: By convincing Germany to focus defenses away from Sicily, the operation saved thousands of Allied lives and accelerated the Italian campaign.

-

Political Consequences: The successful invasion precipitated Mussolini’s downfall and Italy’s eventual defection from the Axis powers.

-

Intelligence Legacy: Mincemeat demonstrated the extraordinary effectiveness of strategic deception, influencing later operations including the D-Day deception plan (Operation Fortitude).

-

Cultural Impact: The operation captured public imagination following the war, inspiring books, films, and ongoing historical interest.

For the architects of the deception, the operation represented their finest hour, though they received little public recognition during the war. Ewen Montagu eventually published “The Man Who Never Was” in 1953 once details were declassified, bringing the extraordinary tale to public attention.

Final Resting Place: The Man Who Never Was

“Major William Martin” received a proper military burial in Huelva, Spain, where his grave can still be visited today. His headstone bears both his fictional name and a reference to the operation that changed the course of World War II.

It wasn’t until 1996 that the British government amended the grave to acknowledge the true identity of the body used in the operation, adding the inscription: “Glyndwr Michael; Served as Major William Martin, RM.”

The Lessons of Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat succeeded by exploiting a fundamental truth about human psychology: people are more likely to believe information they think they’ve discovered themselves than information presented to them directly. By creating circumstances where German intelligence believed they had intercepted secret documents, the British ensured the deception would be all the more convincing.

The operation also demonstrates the power of meticulous attention to detail. Had any single element of Major Martin’s identity seemed suspicious – an inconsistency in his personal items, an irregularity in the documents, or an error in the handling of his body – the entire deception might have unraveled.

In the realm of military intelligence, Operation Mincemeat stands as a testament to how creativity, careful planning, and psychological insight can sometimes accomplish what brute force cannot. A single corpse, carefully dressed and equipped with falsified documents, managed to deceive the Nazi high command and change the course of history.